What is destroying globular clusters?

Globular clusters were formed early in the history of our Milky Way’s history; the 150 or so globular clusters in our galaxy contain many of its oldest stars. Globular clusters are round (hence their name), dense, gravitationally bound collections of stars and can contain hundreds of thousands of stars.

What’s older than globular clusters? Dark matter subhalos! Our galaxy is dominated by dark matter distributed in a halo. Massive supercomputer simulations have shown that regions of higher dark matter density known as subhalos were the seeds for the formation of the galaxy. These subhalos, with millions of solar masses, formed first and supplied the gravity necessary for galaxies to subsequently begin their formation.

Palomar 5 is smaller than most globulars. It was detected only in 1950, in part due to its low mass of only 16,000 solar masses. Palomar 5 is far above the Milky Way’s disk, residing in the dark matter dominated halo, and has been heavily influenced tidally over the past 11 billion years. In its next encounter with the disk, some 100 million plus years into the future, it may even be completely torn apart by tidal interactions.

Palomar 5 shows significant tidal disruption, with a very long stream of stars trailing out of the cluster, pulled out by tidal forces. The length of the stream is several tens of degrees across the sky, some 30,000 light-years in extent. This is greater than the distance from the Sun to the center of the Milky Way. The stream’s mass is 5000 times that of the Sun.

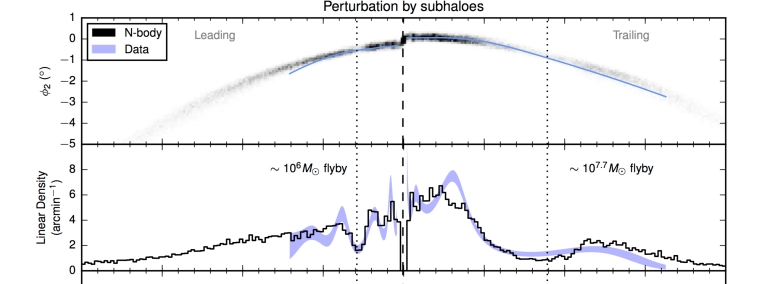

Of great significance are two well defined gaps in the stream. These gaps are very intriguing to astrophysicists, because they may be probes of the nature of the dark matter in our galaxy’s halo.

Upper portion of Figure 9 from Erkal et al. (referenced below). The two gaps are centered on the dotted lines.

Recently three astrophysicists from the Institute of Astronomy at Cambridge University have modeled the stream and these two gaps and described three main possible causes of the gaps: the Milky Way’s bar (our galaxy has spiral arms leading into a central bar), giant molecular clouds, and/or dark matter halos. (Erkal et al. paper in References below).

They find that gravitational interaction from giant molecular clouds might explain the smaller gap, but not the larger one. Interaction from the Milky Way’s bar is another possibility, but might not be the best for producing such clean gaps, that on the face of it, seem to be due to discrete encounters with smaller structures.

Because of the well defined nature of the gaps, the researchers’ preliminary conclusion is that dark matter halos caused both, and especially so in the case of the larger gap. The smaller gap could be caused by giant molecular clouds, but probably not the larger gap.

The leading tail of the star stream (shown on the left side of the figure) has a two degree gap; this is consistent with an interaction from a dark matter subhalo of 1 to 10 million solar masses. The trailing tail has a nine degree gap that is consistent with perturbation of the stream due to a dark matter subhalo of 10 to 100 million solar masses.

Additional data from several planned experiments should allow better discrimination between the possible causes of the gaps. It is very interesting to note that if the smaller gap is due to a sub halo of a few million solar masses, that knowledge in turn can be used to constrain the mass of the dark matter particles to be greater than 2% of the electron rest mass. This would rule out axions as the dominant contributor to dark matter; the axion mass is expected to be much less than 1 electron-Volt (eV) whereas the electron mass is 511,000 eV.

References:

Erkal, D., Koposov S., and Belokurov V. 2016 “A sharper view of Pal 5’s tails” http://arxiv.org/pdf/1609.01282v1.pdf

Kupper, A. et al. 2015 “Globular Cluster Streams as Galactic High-Precision Scales” https://arxiv.org/abs/1502.02658

Kuzma, P. et al. 2014 “Palomar 5 and its Tidal Tails” https://arxiv.org/abs/1411.0776

https://darkmatterdarkenergy.com/2014/02/09/axions-as-cold-dark-matter/