The Higgs boson is considered a necessary part of the Standard Model of particle physics. In the Standard Model there are 3 main forces of nature: the electromagnetic force, the weak nuclear force, and the strong nuclear force. The Standard Model does not address gravity and we do not yet have a proven theory for the unification of gravity with the other 3 forces.

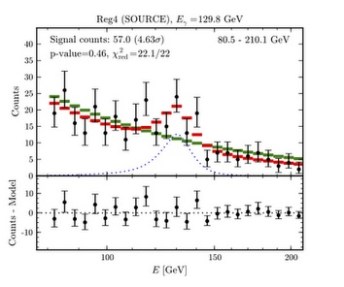

On July 4th CERN, the European particle physics lab near Geneva, announced that two experiments using the Large Hadron Collider accelerator, ATLAS and CMS, have both amassed strong statistical evidence (around 5 sigma) for a new particle. This new particle has a mass of about 126 GeV* and “smells” very much like it is the long sought after, and elusive, Higgs boson. The prediction of the Higgs dates from 1964. For comparison, the proton mass is about 0.94 GeV, so the Higgs is around 134 times more massive. Further work is necessary to determine all of its properties, but at this point it looks as if the new particle decays into other particles in the expected manner. It is these decay products that are actually detected.

This decades-long search has proceeded in fits and starts, principally at CERN in Europe and Fermilab in the U.S., with different accelerators and detectors. Over time the experiments were able to exclude possible masses for the Higgs, since the rate of creation of different decay products varies for different putative masses. By the end of 2011 it looked like there was a preliminary signal, not yet of sufficient statistical strength, but that the mass would have to be in the range of about 115 to 130 GeV.

The CMS detector at the Large Hadron Collider. Credit: Mark Thiessen/National Geographic Society/Corbis

One of my professors, Steven Weinberg, won the Nobel Prize in Physics years ago for his work on unifying the electromagnetic force and the weak force. While the Standard Model and the body of work in particle physics provides a theoretical underpinning for all of the particles which we observe, and their quantum properties, and describes a unification of the strong force (which holds together the quarks inside a proton or neutron) with these other two forces, it also requires an additional mechanism to explain why most particles have non-zero masses.

The Higgs mechanism is the favored explanation, and it predicts a particle as the mediator to provide masses to other particles. The Higgs mechanism is theorized as an all-pervasive Higgs field, which slows down particles as they move through it. As you swim through water you feel a drag that slows you down. A fish with a very hydrodynamic design will feel less drag. In the particle world, more massive ones slow down more than the lighter ones, since they interact more strongly with the Higgs field.

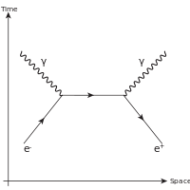

The particle corresponding to this mechanism is known as the Higgs boson. Particles can have quantum spin that is a multiple of ½ or an integer multiple. Bosons have integer multiple spins. Actually the spin of the Higgs boson is zero. All of the force mediator particles such as the photon (spin = 1), which mediates electromagnetism, are bosons.

The Large Hadron Collider is in some sense recreating the conditions of the very early universe by smashing particles together at 7000 GeV, or 7 TeV. The Higgs originally would have been created in Nature in the very early part of the Big Bang, around the first one-trillionth of a second. The appearance of the Higgs broke the unification, or symmetry, between the electromagnetic and weak forces that Steven Weinberg demonstrated are one at very high energies. And the Higgs gave mass to particles.

Without the Higgs mechanism, all particles would be massless, and thus travelling at the speed of light, and structure in the universe – stars, planets, galaxies, human beings, would not be possible. Even the existence of the proton itself requires that quarks have mass, although most of the proton mass comes from the energy of the gluons (strong force mediation particle) and ‘virtual’ quark-antiquark pairs found inside it.

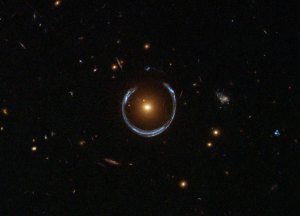

The Higgs boson cannot be the explanation for dark matter for a very simple reason. Dark matter must be stable with a very long lifetime, persisting over the universe’s present age of 14 billion years. It mostly sits in space doing nothing except providing additional gravitational interaction with ordinary matter. The favored candidate for dark matter is the least massive supersymmetric particle; being the least massive, it would have nothing to decay into. Supersymmetry is a theoretical extension beyond the Standard Model. No supersymmetric particles are detected as of yet, but the theory has a lot of support and has the benefit of stabilizing the mass of the Higgs itself.

The Higgs boson, on the other hand, decays very rapidly. There are various decay channels, including into quarks, W/Z bosons, leptons or photons, producing these in pairs (two Zs, two top quarks etc.). Sometimes even four particles are produced from a single Higgs decay. It is these decay products that are actually detected in the Large Hadron Collider at CERN.

There are a few experiments that are claiming to have directly detected dark matter. The favored mass range from the COGENT and DAMA/LIBRA experiments is around 10 GeV for dark matter, much more than a proton, but less than 10% of the Higgs’ mass. Now that the Higgs appears to have been found, work will proceed on confirming and elucidating its properties. And the next great hunt for particle physics may be the direct detection of dark matter particles and the beginning of a determination if supersymmetry is real.

* GeV = Giga-electronVolt or 1 billion electron Volts. 1 TeV (Tera-electronVolt) = 1000 GeV

References:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Higgs_boson

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_Model

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Large_Hadron_Collider

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/physics/blog/2012/07/higgs-fireworks-on-july-4/

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ktEpSvzPROc – Don Lincoln of Fermilab on how we search for the Higgs at particle accelerators

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=r4-wVzjnQRI&feature=related – BBC documentary