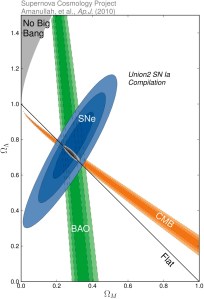

Dark Energy and Matter content of Universe: The intersection of the supernova (SNe), cosmic microwave background (CMB) and baryon acoustic oscillation (BAO) ellipses indicate a topologically flat universe composed 74% of dark energy (y-axis) and 26% of dark matter plus normal matter (x-axis).

The 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics, the most prestigious award given in the physics field, was announced on October 4. The winners are astronomers and astrophysicists who produced the first clear evidence of an accelerating universe. Not only is our universe as a whole expanding rapidly, it is in fact speeding up! It is not often that astronomers win the Nobel Prize since there is not a separate award for their discipline. The discovery of the acceleration in the universe’s expansion was made more or less simultaneously by two competing teams of astronomers at the end of the 20th century, in 1998, so the leaders of both teams share this Nobel Prize.

The new Nobel laureates, Drs. Saul Perlmutter, Adam Riess, and Brian Schmidt, were the leaders of the two teams studying distant supernovae, in remote galaxies, as cosmological indicators. Cosmology is the study of the properties of the universe on the largest scales of space and time. Supernovae are exploding stars at the ends of their lives. They only occur about once each fifty to one hundred years or so in a given galaxy, thus one must study a very large number of galaxies in an automated fashion to find a sufficient number to be useful. The two teams introduced new automated search techniques to find enough supernovae and achieve their results.

During a supernova explosion, driven by rapid nuclear fusion of heavy elements, the supernova can temporarily become as bright as the entire galaxy in which it resides. The astrophysicists studied a particular type of supernova known as Type Ia. These are due to white dwarf stellar remnants exceeding a critical mass. Typically these white dwarfs would be found in binary stellar systems with another, more normal, star as a companion. If a white dwarf grabs enough material from the companion via gravitational tidal effects, that matter can “push it over the edge” and cause it to go supernova. Since all occurrences of this type of supernova event have the same mass for the exploding star (about 1.4 times the Sun’s mass), the resultant supernova has a consistent brightness or luminosity from one event to the next.

This makes them very useful as so-called standard candles. We know the absolute brightness, which we can calibrate for this class of supernova, and thus we can calculate the distance (called the luminosity distance) by comparing the observed brightness to the absolute. An alternative measure of the distance can be obtained by measuring the redshift of the companion galaxy. The redshift is due to the overall expansion of the universe, and thus the light from galaxies when it reaches us is stretched out to longer, or “redder” wavelengths. The amount of the shift provides what we call the redshift distance.

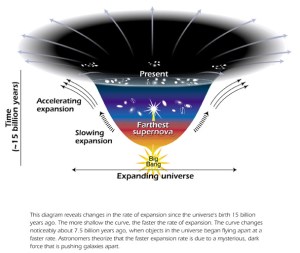

Comparing these two different distance techniques provides a cosmological test of the overall properties of the universe: the expansion rate, the shape or topology, and whether the expansion is slowing down, as was expected, or not. The big surprise is that the expansion from the original Big Bang has stopped slowing down due to gravity and has instead been accelerating in recent years! The Nobel winners did not expect such a result, thought they had made errors in their analyses and checked and rechecked. The acceleration did not go away. And when they compared the results between the two teams, they realized they had confirmed each others’ profound discovery of the reality of a dark energy driven acceleration.

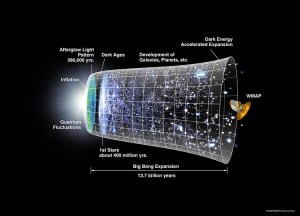

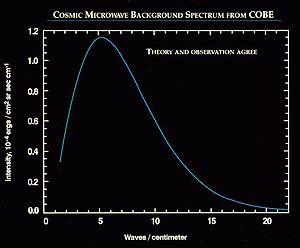

The acceleration result is now well founded since it can be seen in the high spatial resolution measurements of the cosmic microwave background radiation as well. This is the radiation left over from the Big Bang event associated with the origin of our universe.

The acceleration is now increasingly important, dominating during the past 5 billion years of the 14 billion year history of the universe. Coincidentally, this is about how long our Earth and Sun have been in existence. The acceleration has to overcome the self-gravitational attraction of all the matter of the universe upon itself, and is believed to be due to a nonzero energy field known as dark energy that pervades all of space. As the universe expands to create more volume, more dark energy is also created! Empty space is not empty, due to the underlying quantum physics realities. The details, and why dark energy has the observed strength, are not yet understood.

Amazingly, Einstein had added a cosmological constant term, which acts as a dark energy, to his equations of General Relativity even before the Big Bang itself was discovered. But he later dropped the term and called it his worst blunder, after the expansion of the universe was first demonstrated by Edwin Hubble over 80 years ago. It turns out Einstein was in fact right; his simple term explains the observed data and the Perlmutter, Riess, and Schmidt measurements indicate that ¾ of the mass-energy content of the universe is found in dark energy, with only ¼ in matter.

Our universe is slated to expand in an exponential fashion for trillions of years and more, unless some other physics that we don’t yet understand kicks in. This is rather like the ever-increasing pace of modern technology and modern life and the continuing inflation of prices.

We honor the achievements of Drs. Perlmutter, Riess, and Schmidt and of their research teams in increasing our understanding of our universe and its underlying physics. Interestingly, only a few weeks ago, a very important supernova in the nearby M101 galaxy was discovered, and it is also a Type 1a. Because it is so close, only 25 million light years away, it is yielding a lot of high quality data. Perhaps this celestial fireworks display was a harbinger of their Nobel Prize?

References:

http://www.nytimes.com/aponline/2011/10/04/science/AP-EU-SCI-Nobel-Physics.html?_r=2&hp

http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/2011/press.html

http://www.nobelprize.org/mediaplayer/index.php?id=1633 (Telephone interview with Adam Reiss)

http://supernova.lbl.gov/ (Supernova Cosmology Project)

https://darkmatterdarkenergy.wordpress.com/2011/08/31/m101-supernova-and-the-cosmic-distance-ladder/

https://darkmatterdarkenergy.wordpress.com/2011/07/04/dark-energy-drives-a-runaway-universe/