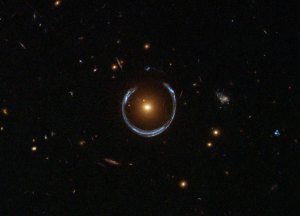

All of our evidence for dark matter is indirect, that is, we deduce the existence of substantial amounts of dark matter – exceeding the amount of ‘ordinary matter’ by 5 times – from its gravitational effects at large distances, on the scale of galaxies, clusters of galaxies, and even across regions of a billion light-years in size.

The generally favored hypothesis is that dark matter is composed of some sort of new weakly interacting massive particle (WIMP). Such a WIMP would not interact via the electromagnetic force or the strong nuclear force, and thus is very hard to detect directly. There are a number of experiments underway attempting to directly detect the elusive particle. The majority of these are earthbound experiments wherein ordinary matter in crystalline form is used as the detector. Three of these experiments are in fact claiming statistically significant detection rates, the DAMA/Libra experiment in Italy, the CRESST experiment based in Germany, and the COGENT experiment in the U.S.

In this class of experiments one is looking to detect a collision of a dark matter particle with an ordinary matter particle, and if detection is successful, to determine the mass of the dark matter particle, as well as its cross-section for collision with ordinary matter. The cross-section is a way of measuring how close the ordinary matter particle and dark matter particle have to approach each other to have a collision event. A collision event produces decay products (additional particles) that the experiments are then able to detect. The results of the 3 experiments named above are still highly controversial, as a number of other similar experiments are not confirming detection, but collectively they may indicate detection of WIMPs with mass in a range around 5 to 40 times the mass of a proton.

Another approach to more directly detecting dark matter (i.e., not through its gravitational effects) is to look for dark matter particles colliding with one another. The number of such events occurring at the Earth’s surface is expected to be quite low, so one must look into the cosmos. Recently some scientists calculated that about one dark matter particle a month on average strikes an atom inside a human on Earth (but not to worry, other background radiation to which we are exposed is much more significant). But we are in a region of over-concentration of ordinary matter; dark matter is spread out on the largest scales. We need to examine much bigger regions to observe dark matter particles striking one another. But look for what, and how?

NASA’s orbiting Fermi Gamma-ray Telescope provides one way. When two dark matter particles collide, depending on the nature of the dark matter particle (is it its own anti-particle), they can possibly mutually annhilate and produce very energetic gamma-ray photons. Gamma rays are at the most energetic end of the electromagnetic spectrum, which includes X-rays, visible light, and radio waves.

Recently the LAT, or Large Area Telescope, which is the main instrument on board the Fermi Gamma-ray Telescope (in orbit) reported on results based on two years of searching for gamma ray production from dark matter annihilation. The method used was to monitor 10 dwarf galaxies that are gravitationally bound to our Milky Way galaxy.

Take a look at this video from NASA Goddard: No WIMPS in Space?

Dwarf galaxies are thought to be good candidates for this type of dark matter search, as they are the remnants of so-called dark matter halos that may have been the first large-scale gravitationally bound objects to form. Larger galaxies in turn grew from multiple such halos coming together, but today’s remaining dwarf galaxies did not get caught up in significant merger activity. They also have mature stellar populations, so there is not a lot of ongoing activity with respect to supernovae or black holes that would produce gamma rays from these other causes.

The international team using the Fermi telescope looked for gamma rays with energies up to 100 billion electron volts (about 100 times the rest mass energy equivalent of a proton), but did not find any that could be clearly attributed to dark matter. The search will continue, gathering more statistics over time and adding additional target dwarf galaxies to their measurements, in the hopes of either finding dark matter through this method, or putting more constraints on its properties.

References:

http://www.cresst.de/darkmatter.php – CRESST experiment

http://cogent.pnnl.gov/ – COGENT experiment

http://people.roma2.infn.it/~dama/web/home.html – DAMA/LIBRA experiment

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fermi_Gamma-ray_Space_Telescope

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dark_matter#Direct_detection_experiments

http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/GLAST/news/dark-matter-insights.html – Fermi Gamma-ray telescope