I was at the dentist this week. Don’t ask, but they took 3 digital X-Rays.

One of the most significant methods by which we detect the presence of dark matter is through the use of X-ray telescopes. The energy associated with these X-rays is typically around an order of magnitude less than those zapped into your mouth when you visit the dentist.

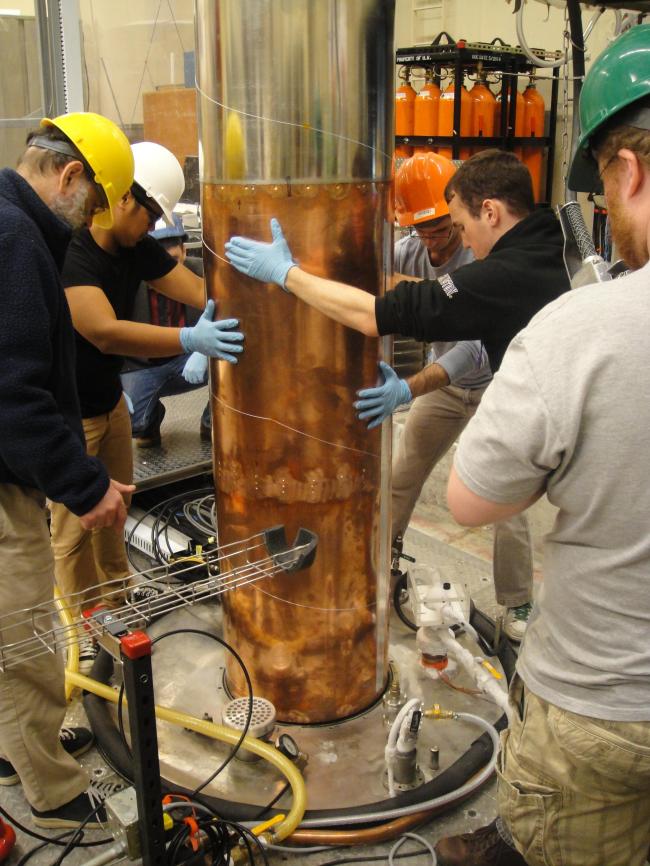

Around 50 years ago scientists at American Science and Engineering flew the first imaging X-ray telescope on a small rocket. At a later date, I worked part-time at AS&E, as we called it, while in graduate school. One major project was a solar X-Ray telescope mounted in SkyLab, America’s first space station. This gave me the wonderful opportunity to work in the control rooms at the NASA Johnson Space Center in Houston.

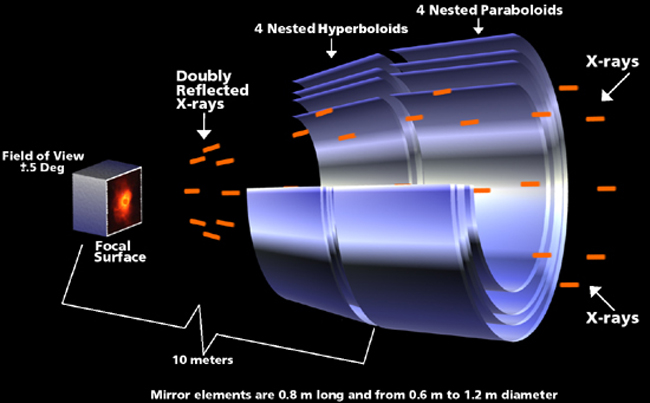

X-rays are absorbed in the Earth’s atmosphere, so today X-ray astronomy is performed from orbiting satellites. X-ray telescopes use the principle of grazing incidence reflection; the X-rays impinge at shallow angles onto gold or iridium-coated metallic surfaces and are reflected to the focal plane and the detector electronics.

Schematic of grazing incidence mirrors used in the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Credit NASA/CXC/SAO; obtained from chandra.harvard.edu.

How does dark matter result in X-rays being produced? Indirectly, as a consequence of its gravitational effects.

One of the main mechanisms for X-ray production in the universe is known as thermal bremsstrahlung. Bremsstrahlung is a German word meaning ‘decelerated radiation’. A gas which is hot enough to give off X-rays will be ionized. That is, the electrons will be stripped from the nuclei and move about freely. As electrons fly around near ions (protons and helium nuclei primarily) their mutual electromagnetic attraction will result in some of the electrons’ kinetic energy being transferred to radiation.

The speed at which the electrons are moving around determines how energetic the produced photons will be. We talk about the temperature of such an ionized gas, and that is proportional to the square of the average speed of the electrons. A gas with a temperature of 10 million degrees will give off approximately 1 kiloVolt X-rays (hereafter we use the KeV abbreviation), and a gas with a temperature of 100 million degrees will radiate 10 KeV X-rays. One eV converts to 11,605 degrees Kelvin (or we can just say Kelvins).

Chandra X-ray Observatory prior to launch in the Space Shuttle Columbia in 1999. NASA image.

So how can we produce gas hot enough to give off X-Rays by this mechanism? Gravity, and lots of it. The potential energy of the gravitational field is proportional to the amount of matter (total mass) coalesced into a region and inversely proportional to the characteristic scale of that region. GM/R, simple Newtonian mechanics, is sufficient; no general relativistic calculation is needed at this point. G is the gravitational constant and M and R are the cluster mass and characteristic radius, respectively.

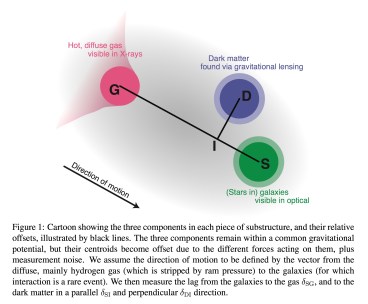

A lot of mass in a confined region – how about large groups of clusters and galaxies? It turns out we need of order 1000 galaxies for a rich cluster and this will do the trick. But only because there is dark matter as well as ordinary matter. There are three main matter components to consider: galaxies, hot intracluster gas found between galaxies, and dark matter. The cluster forms from gravitational self-collapse from a region that was of above average density in the early universe. All the over dense regions are subject to collapse.

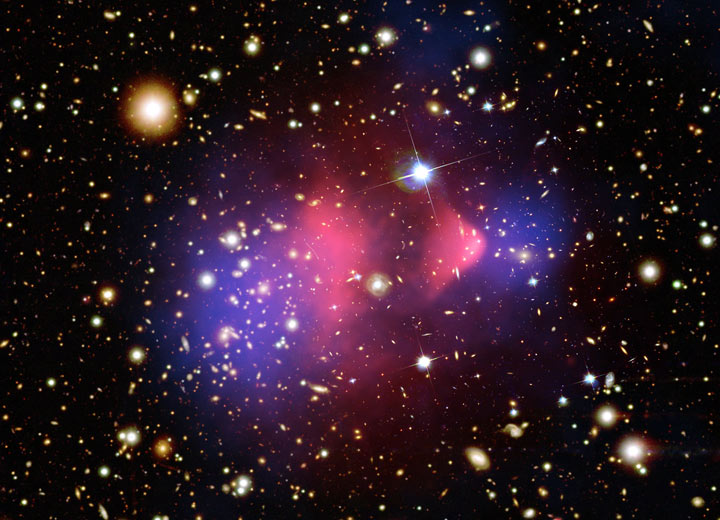

The “Bullet Cluster” is actually two colliding clusters. The bluish color shows the distribution of dark matter as determined from the gravitational lensing effect on background galaxy images. The reddish color depicts the hot X-ray emitting gas measured by the Chandra X-ray Observatory.

(X-ray: NASA/CXC/CfA/M.Markevitch Optical: NASA/STScI; Magellan/U.Arizona/D.Clowe Lensing Map: NASA/STScI; ESO WFI; Magellan/U.Arizona/D.Clowe)

The optically visible galaxies are the least important contributor to the cluster mass, only around 1%! Galaxy clusters are made of dark matter much more than they are made out of galaxies. And secondarily, they are made out of hot gas. The ordinary matter contained within galaxies is only the third most important component. The table below gives the typical 90 / 9 / 1 proportions for dark matter, hot gas, and galaxies, respectively.

Three main components of a galaxy cluster (Table derived from Wikipedia article on galaxy clusters)

Component Mass fraction Description

Galaxies 1% Optical/infrared observations

Intergalactic gas 9% High temperature ionized gas – thermal bremsstrahlung

Dark matter 90% Dominates, inferred through gravitational interactions

The intracluster gas has two sources. A major portion of it is primordial gas that never formed galaxies, but falls into the gravitational potential well of the cluster. As it falls in toward the cluster center, it heats. The kinetic energy of infall is converted to random motions of the ionized gas. An additional portion of the gas is recycled material expelled from galaxies. It mixes with the primordial gas and heats up as well through frictional processes. The gas is supported against further collapse by its own pressure as the density and temperature increase in the cluster core.

The temperature which characterizes the X-ray emission is a measure of gravitational potential strength and proportional to the ratio of the mass of the cluster to its size. Typical X-Ray temperatures measured for rich clusters are around 3 to 12 KeV, which corresponds to temperatures in the range of 30 to 130 million Kelvins.

There is another way to measure the strength of the cluster’s gravitational potential well. That is by measuring the speed of galaxies as they move around in somewhat random fashion inside the cluster. The assumption, which is valid for well-formed clusters after they have been around for billions of years, is that the galaxies are not just falling into the center of the cluster, but that their motions are “virialized”. This is the method used by Fritz Zwicky in the 1930s for the original discovery of dark matter. He found that in a certain well known cluster, the Coma cluster, that the average speed of galaxies relative to the cluster centroid was of order 1000 kilometers/sec, much higher than the expected 300 km/sec based on the visible light from the cluster galaxies. This implied 10 times as much dark matter as galactic matter. This early, rather crude measurement, was on the right track, but fell short of the actual ratio of dark matter to galactic matter since we now know that galaxies themselves have large dark matter halos. The X-ray emission from clusters was discovered much later, starting in the 1970s.

The two methods of measuring the amount of dark matter in Galaxy clusters generally agree. Both the galaxies and the hot intracluster gas are acting as tracers of the overall mass distribution, which is dominated by dark matter. Galaxy clusters play a major role in increasing our understanding of dark matter and how it affects the formation and evolution of galaxies.

In fact if dark matter was not 5 times as abundant by mass as ordinary matter, most galaxy clusters would never have formed, and galaxies such as our own Milk Way would be much smaller.

References

Wikipedia article “galaxy clusters”.

“X-ray Temperatures of Distant Clusters of Galaxies”, S. C. Perrenod, J. P. Henry 1981, Astrophysical Journal, Letters to the Editor, vol. 247, p. L1-L4.

“The X-ray Luminosity – Velocity Dispersion Relation in the REFLEX Cluster Survey”, A. Ortiz-Gil, L. Guzzo, P. Schuecker, H. Boehringer, C.A. Collins 2004, Mon.Not.Roy.Astron.Soc. 348, 325; http://arxiv.org/abs/astro-ph/0311120v1