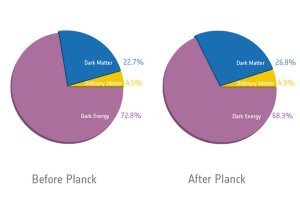

Around 27% of the universe’s mass-energy is due to dark matter, according to the latest Planck satellite results; this finding is consistent with a number of other experiments as well. This is approximately 6 times more than the total mass due to ordinary matter (dominated by protons and neutrons) that makes up the visible parts of galaxies, stars, planets, and all of our familiar world.

The most likely explanation for dark matter is some kind of WIMP – Weakly Interacting Massive Particle. The amount of deuterium (heavy hydrogen) produced in the very early universe rules out ordinary matter as the primary explanation for the various “excess” gravitational effects we see in galaxies, groups and clusters of galaxies and at the largest distance scales in our observable universe.

WIMPs are thought to be a class of new, exotic particles, beyond the Standard Model. A favored candidate for dark matter is the lightest supersymmetric particle, although supersymmetry is as of yet unproven. The lightest such particle would be very stable, having nothing into which it could decay readily. A mass range of 5 to 300 GeV or so is the range in which most of the direct detection experiments looking for dark matter are focused (1 GeV = 1 giga-volt is a little more than the mass of a proton).

But there would certainly be more than one kind of such WIMP formed in the very early universe. These would be heavier particles, and most would quickly decay into lighter products, but there might still be some heavier WIMPs remaining, provided their lifetime was sufficiently long. Particle physicists are actively working on models with more than one component for dark matter, typically two-component models with a heavy particle above 100 GeV mass, and a lighter component with mass of order 10 GeV (more or less).

In fact there are observational hints of the possibility of both a light dark matter particle and a heavier one. The SuperCDMS team has announced a possible detection around 8 or 9 GeV. The COGENT experiment has a possible detection in the neighborhood of 10 GeV, and in general agreement with the SuperCDMS results.

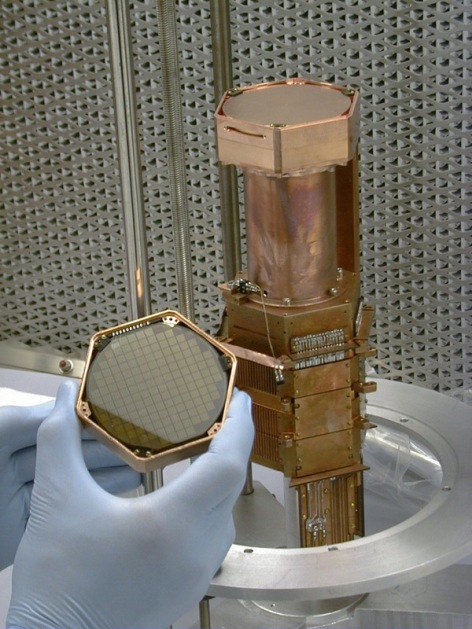

Fermi satellite payload, photo credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

Fermi satellite payload, photo credit: NASA/Kim Shiflett

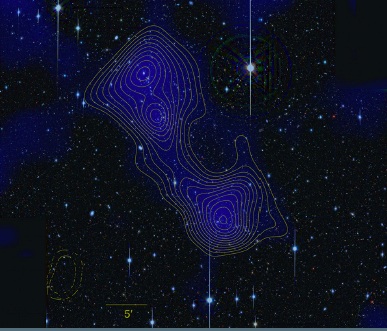

At the heavier end, the Fermi LAT gamma-ray experiment has made a possible detection of an emission line at 130 GeV which might result from dark matter decay. A pair of such gamma rays could be decay products from annihilation of a heavier dark matter particle with mass around 260 GeV. Or a particle of that mass could decay into some other particle plus a photon with about half of the heavy dark matter mass, e.g. 130 GeV.

Kajiyama, Okada and Toda have built one such model with a light particle around 10 GeV and a heavier one in the 100 to 1000 GeV region. They claim their model is consistent with the observational limits on dark matter placed by the XENON 100 experiment.

Gu has developed a model with 2 dark matter components with magnetic moments. Representative values of the heavy dark matter particle mass at 262 GeV and the lighter particle mass at 20 GeV can reproduce the observed overall dark matter density. He also finds the decay lifetime for the heavier particle state to be very long, in excess of 10^20 years, or 10 billion times the age of the universe, thus in this model the heavy dark matter particle easily persists to the present day. In fact, he finds that the heavy particle dominates with over 99% of the total mass contribution to dark matter. And a heavy dark matter particle with the chosen mass can decay into the lighter dark matter particle plus an energetic 130 GeV gamma ray (photon). This might explain the Fermi LAT results.

Furthermore, the existence of two highly stable dark matter particles of different masses would help explain some astrophysical issues related to the formation of galaxies and their observed density profiles. Mikhail Medvedev has numerically simulated galaxy formation using supercomputers, with a model incorporating two dark matter components. This model results in a better fit to the observed velocities of dwarf galaxies in the Local Group than does a model with a single dark matter component. (The Local Group includes our Milky Way, the Andromeda galaxy, the Magellanic Clouds and a number of dwarf galaxies.) His model also helps to explain the more flattened density profiles in galaxies and the smaller numbers of dwarf galaxies actually observed relative to what would be predicted by single dark matter component models.

Occam’s razor says one should adopt the simplest model that can explain observational results, suggesting one should add a second component to dark matter only if needed. It seems like a second dark matter component might be necessary to fully explain all the results, but we will require more observations to know if this is the case.

References:

http://prd.aps.org/abstract/PRD/v88/i1/e015029 Y. Kajiyama, H. Okada and T. Toda 2013, “Multicomponent dark matter particles in a two-loop neutrino model”

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2212686413000058

P. Gu 2013, “Multi-component dark matter with magnetic moments for Fermi-LAT gamma-ray line”

http://arxiv.org/pdf/1305.1307v1.pdf M. Medvedev 2013, “Cosmological Simulations of Multi-Component Cold Dark Matter”